I don’t know what the limit is for sharing.

I’ve written posts and blogged and revealed intimate details about my life before. There are always a few people that are shocked when I reveal something personal, when I share a little about the turmoil inside; but I always feel like I’m the kind of person who wears everything on my sleeves. My face betrays me, my eyes are too open, my soul somehow whispers to others in ways I can’t silence. I showed this post to my wife before publishing, and she wondered, how is it that I can say all of these deeply hidden things to everyone and not her first? I could only respond that I feel like the world is trying to strangle me, and in the few moments when the grip loosens I feel compelled to yell out everything I can before life kills me.

A week or so ago, I posted something on Facebook about being in the middle of a depressive episode, and I didn’t hold back. The post was up for about an hour, but the feedback was immediate and overwhelming. I got calls in the middle of the night from the USA, texts from friends, messages from those people you connected with in the past but time didn’t allow you to stay in touch with; and this was all while I was deep in the middle of one of the worst depressive episodes I’ve ever had, and the worst one since I made aliyah.

I couldn’t respond. I ignored the phone calls. My wife woke up in the middle of the night because they called her, afraid of what I might have done. I told her the usual lie that I was ok, that I posted something and immediately deleted it. I overshared, or rather, I shared and was unready for the deluge of responses that sharing would entail.

So what do I say? Where do I begin? Should I even say anything at all to account for my posts and sudden disappearance?

It’s been two weeks now since that post, and I’m almost out of the episode. There are moments where I still feel depressed, where my bed calls to me as the only safe place, but I can take care of myself again. This time reminds me of how I was after I had my last real breakdown before I was diagnosed, having to get back into the habits of a normal person. Making daily goals that are achievable, but so pathetic that you hate how low you’ve sunken. Nothing is more degrading to someone who defines himself by his achievements than to have brushing your teeth, showering, and eating become major accomplishments for a day. Looking into the mirror and knowing that shaving earns a golden star obliterates one’s soul.

I’ve written before about being bipolar, or at least shared it publicly on social media, but I don’t think I’ve ever really talked in-depth about what it’s like. Therapists always tell me to say that “I have bipolar disorder,” not that, “I am bipolar.” To make me reaffirm that I am not my disease. Someone is not cancer. Someone is not diabetes. Someone is not high blood pressure. So why should this be any different?

Sometimes it’s hard to make that distinction though, even when I desperately need to. For so long, I went undiagnosed and floundering in the ebbs and flows of mania and depression. I had nothing to point to whenever the gears in my mind started to catch, when the wires frayed; I could only assume that it was just me. I molded my personality around my disorder, or maybe it was the other way around; either way, it feels like it’s impossible to separate the two.

So, I want to try and do the impossible, or at least it seems so to me: I want to try and explain what it’s like to be depressed and bipolar in a foreign country, to be in an episode as an oleh.

These past two weeks have been hard, harder than the rest of my time here so far. I don’t want to go into details as to what made them hard, to respect the privacy of those involved; but needless to say I pushed my emotional reservoirs past their capacity.

At a certain point, the stress becomes unbearable, and some hidden switch in the recesses of my brain just switches off and an entirely new set of pathways starts flickering on. The depression that I manage to keep down with all the tricks and techniques of therapy and mindfulness bursts out, and it feels like you’re a passenger in an airplane that’s just taken a nosedive. You feel like you have absolutely no control. You can’t think clearly, all of the normal ways that a person perceives and responds to stimuli change. You become paranoid, you can’t believe anyone’s good intentions, you only see the darkness that you’re barrelling deeper and deeper into. It literally feels like something is slowly sucking out all of the light in your life, and you can feel the blood in your veins growing colder and colder.

All of the suicidal thoughts that you push away, the ones that you treat like birds passing by in the sky, become billboards that get larger and larger as you go deeper into the tunnel. Walking along you would see a bird and just acknowledge it was there, but move on. You used to be able to just shift your attention, but slowly all you can focus on is the pain and whatever solution you can apply to end the sadness that’s crushing you. The single bird is now hundreds of birds on every power line around you on fall night, cawing and blaring out the message: end it, end it, end it. You look around in your car and even blaring the horn can’t drown out the growing decibel level of the hordes of birds yelling directly at you.

You signpost, you say things obliquely or covertly to try and cry for help, something to draw attention to how much you’re suffering. The problem is that when you pass the point where a friend’s message can’t shake you out of it, when you’re so deep in the hole that that almost nothing external can get you out. You ignore people, you don’t look at your friends’ messages and texts, you ignore calls from your family, you tell your spouse that you just can’t handle speaking to anyone. Their well-meaning love from thousands of miles away falls on ears deafened by the noise-cancelling headphones of despair. Every single person saying that they care, that they love you, that you give them strength feels like another person to disappoint, to let down, to make ashamed. Your warped thinking doesn’t allow you to see their love, their warmth; all you can see are people that you wish you didn’t have to bother, that you wish didn’t fret over you, that you think would be better off if they didn’t have that one pathetic friend that they have to worry about. You start to wish that you had no friends, no family, no one that gives a damn about you so that when you eventually decide to go, no one will be for the worse.

At a certain point, you’re not even sad, you just feel the absence of anything good or happy. This is where some people start to self-harm, just to feel something, anything to focus on besides the depression; better to feel the acute and distracting physical pain of a blade across the skin than the deeper existential despair of feeling like you are slowly dying. That didn’t happen this time, but it has in the past. The cuts make you feel like you can take control of some kind of pain, something immediate and obvious. Your thoughts are meaningless when confronted by the deep redness of your own blood and the physical anguish of each slice. Macabre as it is, watching the blood flow from a fresh cut and warm blood is like a blanket, something to put between your immediate existence and the existential doom around you.

You spend your days holed up in a room, stuck to your bed. You cover face with your blanket, trying to make a physical shield between you and the utter desolation that wants to smother you. You try and recreate the womb, the one place you were ever truly safe (but maybe that’s where it all started in the first place). You stop eating, or at least limit meals to when the pain becomes too much for you to say no. You stop bathing, you stop taking care of yourself. Slowly, you become closer and closer physically to the corpse that you feel like.

You feel like giving up. Whatever that means to you, whatever has to happen, you just want the pain to stop. Your warped thinking, your addled mind, pushes you to ponder extreme answers to temporary problems.

You spend days on the precipice of life and death, not knowing where you are. You feel utterly and completely lost, abandoned, and unsure of everything. You wonder, you yell, you curse G-d for what feels like a life destined for nothing but pain. You start to think that the endless cycles of sadness, normality, joy, and insanity will never end; you start thinking that the roller coaster will never end, that there will never be a moment of peace and calm. Who wants to live a life where tranquility is outweighed by the tug of war between mania and depression? Instead of the curse of knowing the day of your death, all you know is that the future is paved with more episodes of unknown length. I’ve seen many things in my life, I’ve stared death in the face, and nothing is scarier than not knowing whether the next month, the next week, or the next day will see the moment when you’re finally put into a straightjacket, hauled off to the hospital, and thrown into a padded room. It’s one thing to see the end, its an entirely different thing when you don’t know if you can even trust the things your eyes are seeing, whether the demon in front of you is really there.

Then, a small thing (it’s always a small thing), somehow manages to pierce the tiniest of holes in the dark canopy to let in just enough light to orient you. In my case, it was a few messages from a man from the East End of London texting me about my new job, and my inability to not read his texts without thinking of myself speaking in his very specific dialect. It’s a couple of emojis in a text from someone who’s only known you a week to somehow pull you out of it. You see that, and you grab for the light. You see the messages everyone else has sent and you see them for the ropes to the sunlight that they are. You slowly pull yourself up, you shake off the faulty mechanics of a depressed brain, and you start to see the light beyond the false firmament.

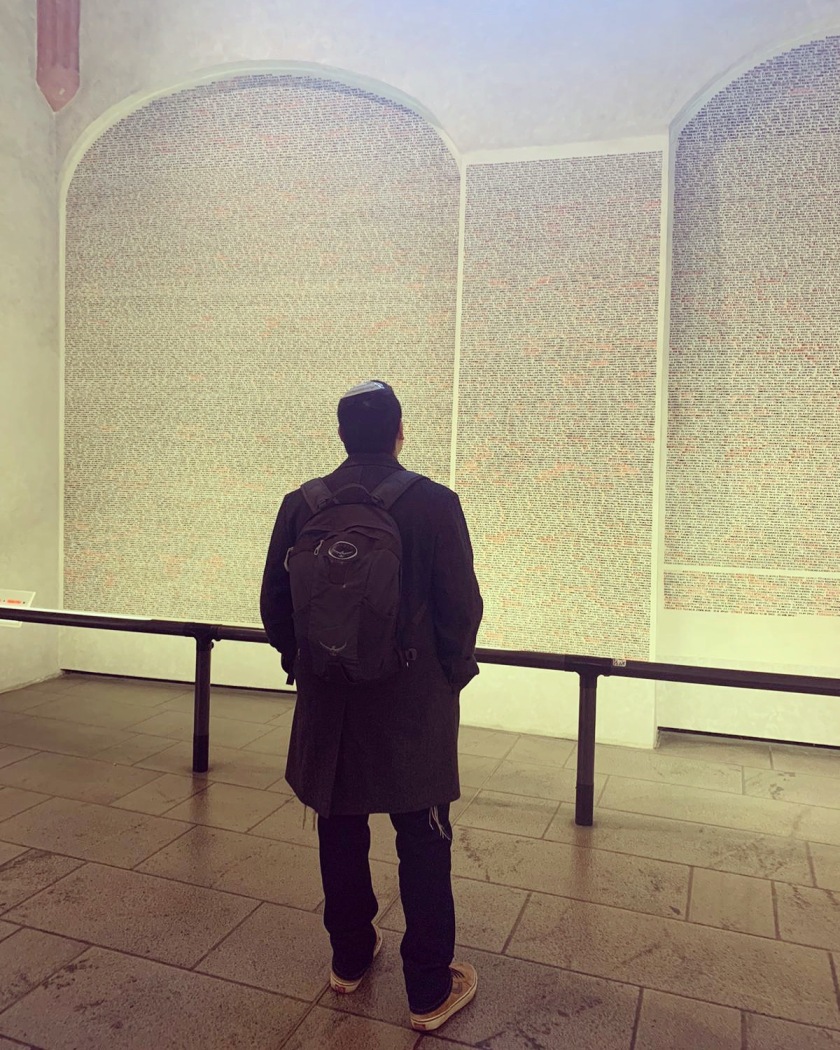

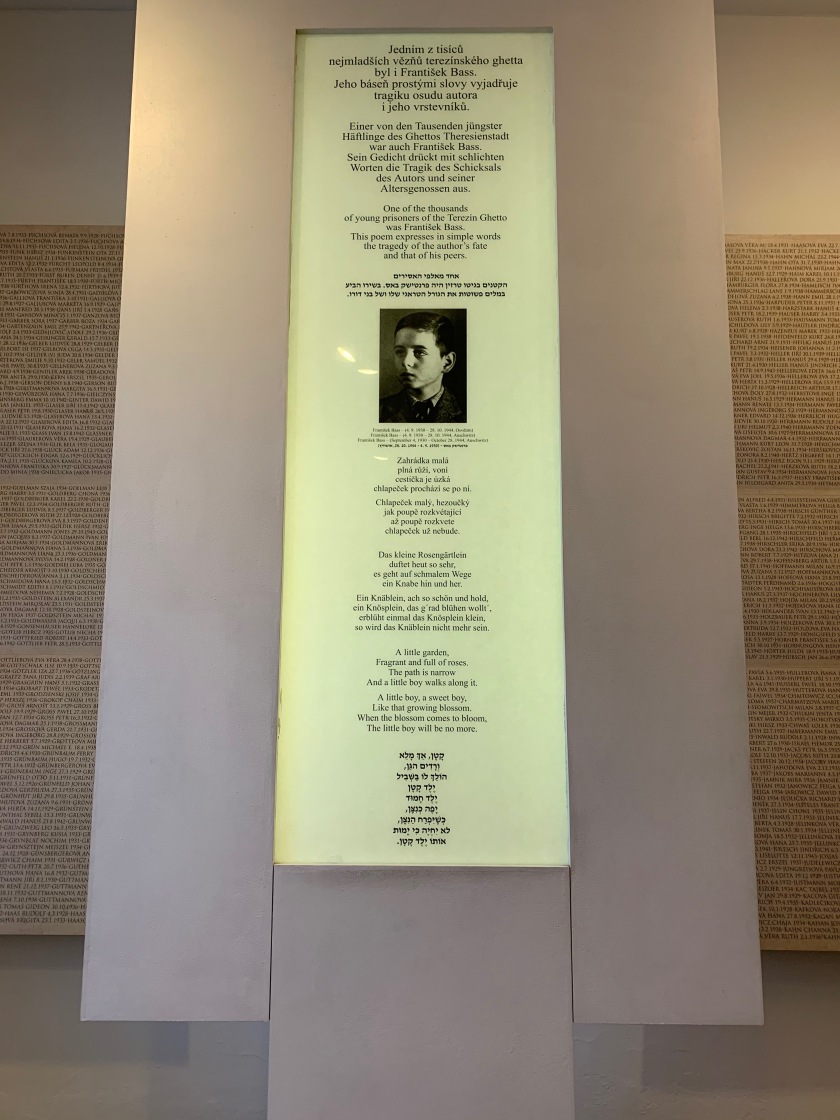

Just like that, you add another name to the list of people who’ve saved your life but don’t know it. Then, you add all of the names of the people that first reached out, the people you were to blinded by pain to see and add them. Slowly, the list becomes a web of names and faces of the people that love and care, the people that are there to catch you when you start to fall.

That’s where I am today, I am trying to reach for that light. I’m still not out of it, but I think that I’m on my way up. Life in Israel is stressful, aliyah is stressful, and being bipolar magnifies all of that times a thousand, but it’s not the end of my story. I will succeed in this country, I will fulfill my dreams.

Im tirtzu, ein zo agada. If you will it, it is not a dream.

I will flourish here, I will make this a better place, I will tell my grandchildren one day that their saba got through it all so that they would be able to live in Jewish country in our land. I will not let this stop me, I cannot.

I have to thank my friends and family who reached out and called, texted, and messaged me. I have to thank my spouse. I have to thank you all.

And I have to thank a man from the East End for saving my life, another hidden saint who will never know the kindness he did for me.

Love y’all.