Last week, I walked through a little town outside of Prague, home to a few thousand people living close to the forests of Bohemia. Old pre-war buildings lined the small streets. I sat in a little park and watched the people pass by. A woman walked her two young children home from school, the children pausing to look at me, a strange man with a little fabric disc on top of his head, strange strings peeking out from the bottom of his long coat. They passed in front of a rather unremarkable building, save for one word written atop the entranceway in Hebrew letters: Yizkor, Remembrance.

That little town is called Terezín, and it once housed the concentration camp I know by the German name: Theresienstadt.

Throughout our journey in Prague, I took lots of pictures and posted them immediately to social media (what do you expect, I’m a millennial). My wife and I really enjoyed Prague, especially the Jewish history of the town. The old Jewish Quarter is one of the biggest tourist attractions in the city, and the Alt-Neu (Old-New) Synagogue is the oldest continuously used synagogue in Europe. We encountered plenty of Jewish tourists as we visited the old synagogues, the cemetery, and the few kosher restaurants; but I was overwhelmed by the amount of non-Jews exploring the remains of a once vibrant community, home to some of the greatest rabbis in Europe’s history.

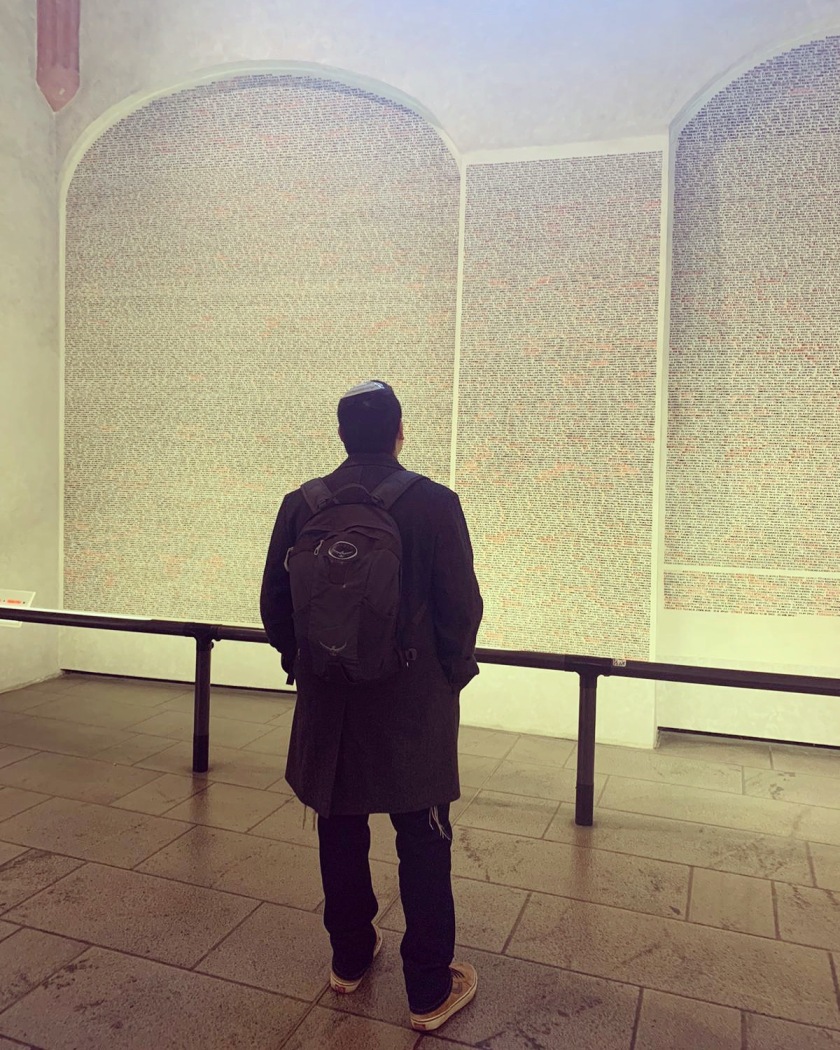

It was surreal, to be both the tourist and the subject of tourism. To go into a synagogue that was once used for so many life events only to be turned into a museum of Judaism, or a memorial to the victims of the Shoah. One particular synagogue had all of the names of Czech Jews murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators, and the sight was staggering.

But that was nothing to seeing the real thing in person.

To be honest, I didn’t know what to expect, how I would feel. What would go through my mind as I walked through the places where tens of thousands met their deaths, and even more waited to be sent off to the death camps. I didn’t know if I would be able to hold it together. Honestly, I was afraid of it all. As a bipolar person, speaking for myself specifically, I feel things more intensely than the average person. My emotional sensitivity is always jacked up to 11, and I didn’t know how confronting all of the death, the suffering, and my identity’s connection to all of that would affect me.

What I definitely did not expect were the stares. Out of the hundreds of visitors that day during the few hours we were there, I didn’t see a single other obviously Jewish person, save for one guy who I knew was Jewish from a chance encounter earlier in the day. My wife, in her wig and hat, can pass as just another tourist, but my kippah and tzitzit mark me from a hundred feet away as an Orthodox Jew; and let me tell you that I could feel the stares from that far away. Huge groups of teenagers, speaking English, French, German, Czech, passed us by and every one of them stopped talking for a moment to see me. I felt like every single pair of eyes was on me, probing me, wondering what I was thinking. I couldn’t help but look back at some of them, and whenever we locked eyes, a flood of emotions flashed back and forth between us. From them, I felt shock, curiosity, uneasiness, tension, and sometimes a tinge of guilt. All they got from me was hardness, eyes made empty of light by the sight of ARBEIT MACHT FREI on the top of the gateway, harshened by the sight of the pits where they shot and buried thousands of my brothers and sisters, drained by crematoriums where they burned the bodies and scattered their ashes in the river. Could I ever drink from the water there ever again knowing that its soil must still have the essence of the Jews of Bohemia in its banks?

Even now, it’s difficult to put into words what I felt. There was the annoyance and anger as my tour guide, in her little scripted walk, kept on saying “the Jews” as if we were an ancient object and not a living person standing right in front of her. I can tell you about the rage I felt when I saw people laughing or smiling in a place made bitterly holy by the thousands of martyrs slain on its grounds. Or about the tears I shed as I placed rocks by the memorials, the mass graves, and as I lit a candle on the car of one of the ovens to remember at least one soul devoured by the flames of that dreadful stone building. I felt disbelief that people could still live there, in a place so associated with death and misery, that children could play just a short walk from where countless children met their deaths from starvation, from disease, and from torture.

But I can’t really express what I felt as I walked the grounds of the camps, this overwhelming numbness to it all. Maybe it was my mind’s way of protecting me from it all, from having to process it all emotionally. It was hard to speak there, I felt like my throat closed up to avoid having to breathe the air that still held the cries and screams of Jews facing the insurmountable and the unthinkable.

I’ve been to funerals, I’ve buried my own mother, I’ve buried friends, I’ve seen children’s caskets lowered into the earth, but the sadness and despair I felt there were incomparable. With a funeral, there’s an order, something created to give you closure, something to comfort you. At Theresienstadt, all you’re left to see is that was left over from the killings, it was something we were never meant to really see. Theresienstadt was supposed to be the model camp to show to the world that the Nazis were treating us humanely, a temporary charade. The reality is that tens of thousands of my people were killed in this camp, or waited to be sent to their death in another camp, and we have no way to remember them other than visiting these horrible places.

Near the crematorium, there was a memorial cemetery for the victims, and monuments. They were for the people that they knew that died there, but at the end of the cemetery there were graves unlike any I’ve see before. There were all black, set on a slanting hill, literally standing in contrast with the greying tombstones in the regular cemetery. They were the graves put up by surviving family members who never knew where their loved ones died, or when, or how. They just knew that they were gone, and they needed something to at least focus on as a place of mourning and sorrow. I think that is what that whole place was like. We as a people lost so many, just completely lost, people and communities. Entire villages lost to the flames, devoured by the monsters. It is something so unfathomably large, horrible, and inescapable that we have to focus on something tangible just to be able to process a fraction of the trauma, whether it’s a stone monument, a grave, a tree planted in remembrance, or even the killing grounds themselves.

I’m still processing what happened there, what I saw. In my 29 years, I’ve seen things that will forever be burned into my eyes. I am not trying to brag, and honestly I would give up many of my better memories to be able to forget some of the horrible ones. I’ve lived on the edge of death, on the edge of sanity, and through deep and profound loss. I’ve seen and heard things that no one my age should have seen by now, things that no man should have to see, stories that I must bear for the rest of my life. This place stands apart, a place filled with death, with stares, with hardness, and with feeling so lost in the deaths of millions. There are times I’ve felt small because of the grandness of the world, but this was one where I felt emptied by the vastness of the suffering. I don’t know if I could ever go back, but I think everyone should go at least once in their lives.

I do know that visiting that place made me realise even more that I need to be here, living my life to the fullest. Too many good people, innocent people, Jews of every age and background were murdered, slaughtered, butchered, erased. I need to live my life for them, for the Jews of Theresienstadt, for the six million, and for the countless future generations stolen from them. I need to live proudly, in a Jewish country, and shape the world so that their fates are never repeated. I need to live so that they are never forgotten, so that those buildings in Terezín will never become just buildings.

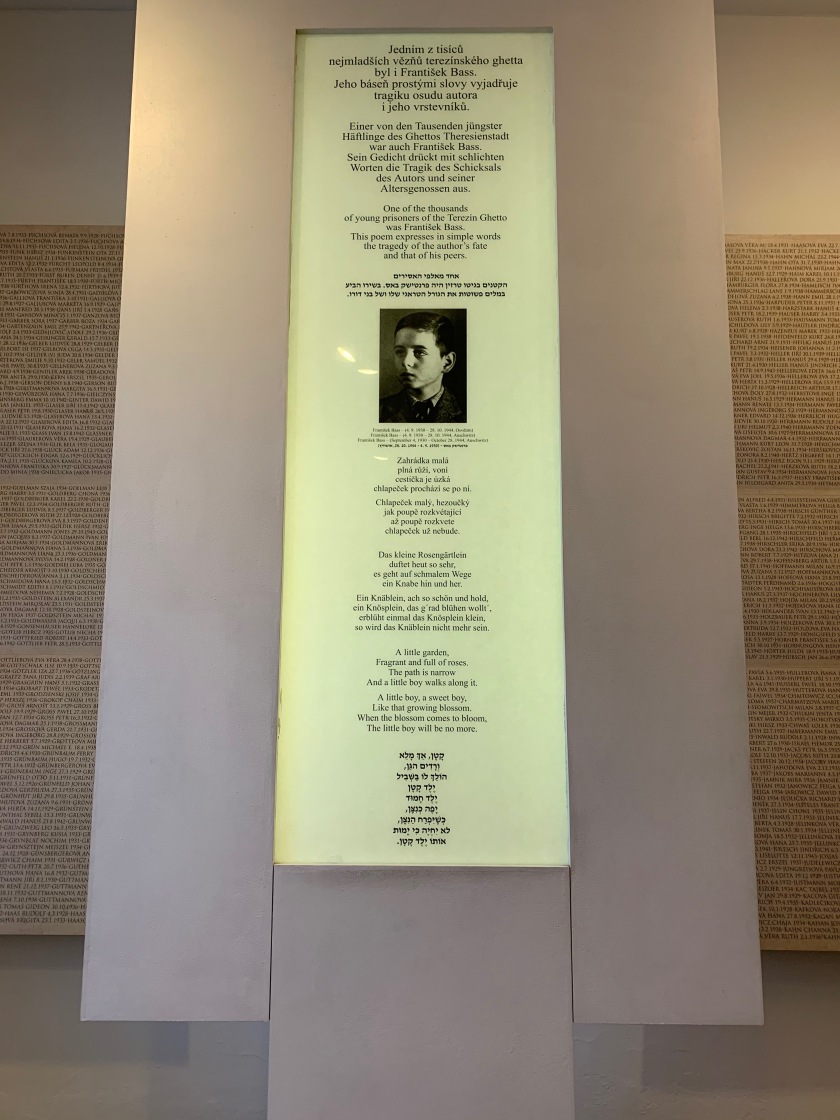

I can’t find the right words to end this, so I’ll end this with a poem from a boy named František Bass, born 4 September, 1930, held in Theresienstadt, died in Auschwitz on 28 October, 1944, age 14.

A little garden,

Fragrant and full of roses.

The path is narrow

And a little boy walks along it.

A little boy, a sweet boy,

Like the growing blossom.

When the blossom comes to bloom,

The little boy will be no more.